The Four-Sentence Letter Behind the Rise of Oxycontin

In 1980, the New England Journal of Medicine published a four-sentence letter written by Jane Porter and Hershel Jick, M.D., describing addiction-related outcomes for the Boston University Medical Center’s patients who had been prescribed opioids. The letter states that out of the 11,000+ patients who received opioid medications, only two of them ever developed a dependence on the drug, and only one of these was a ‘major dependence’.

Although it was published in what many consider to be the world’s most prestigious Medicine Journal, Dr. Jick didn’t think much of it at the time. A conversation with Jick about the letter is detailed in the novel Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic (Dreamland) by Sam Quinones. In it, Jick tells Quinones that the letter’s study is at the bottom of a long list of studies he has performed since then, and that the letter didn’t attract any attention for the rest of the 1980’s. It went seemingly unnoticed for so long that its author had all but forgotten about it.

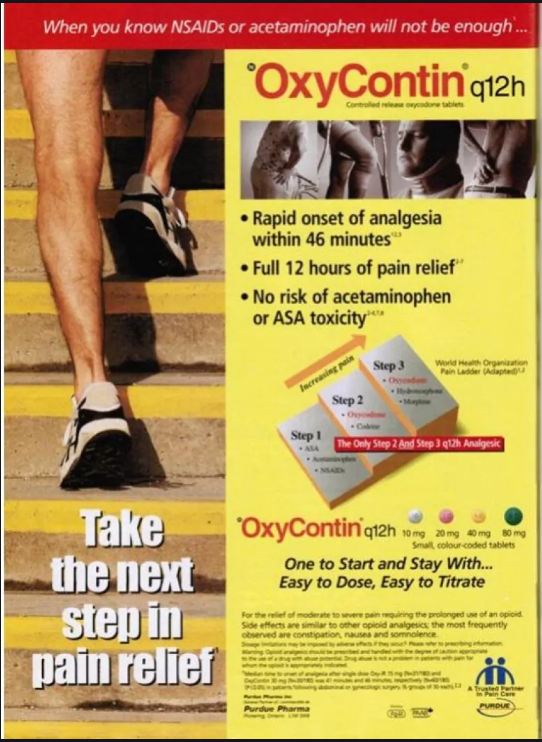

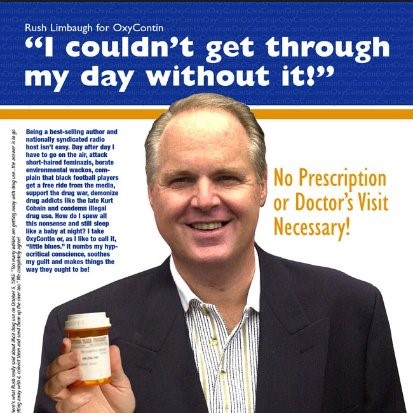

That was until Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of prescription opioids, began to cite the letter as evidence for the safety of Oxycontin.

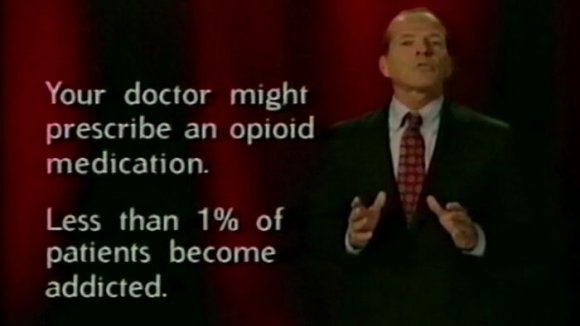

“The rate of addiction for patients who are treated by doctors is much less than 1%”, touts an Oxycontin TV commercial. “They don’t wear out – they go on working. So these drugs, which I repeat, are our strongest pain medications, should be used much more than they [currently] are for patients in pain”.

On the surface, this commercial is similar both in structure and in content to thousands of other commercials broadcast daily over national television. This aspirin commercial, for example, presents a problematic situation and suggests that the solution is already available. In the case of this commercial, that solution is Bayer Low-Dose Aspirin, which the commercial claims prevents 1 out of 3 heart attacks.

The OxyContin commercial follows the same structure. Although the whole of the commercial outside the clip linked above is extremely difficult to find, the clip alone presents a problematic situation (patients in pain needing strong painkillers) and suggests the solution is already available (OxyContin), while citing the drug’s supposed 1% addiction rate. For the average TV viewer, there’s nothing wrong with this commercial. But peel back its unremarkable exterior, and the cracks start to show.

Not having access to the entire OxyContin commercial means we cannot say with 100% certainty that it was targeted at the general public, but being part of a commercial that was broadcast nationally strongly suggests this. Thus, we can assume that its intended audience was individuals suffering from chronic pain. Several aspects of the OcyContin commercial support this theory:

- It highlights the exceptional strength of the medication, pandering to long-time sufferers from chronic pain who have had limited success with other medications.

- It highlights the 1% addiction rate, pandering to sufferers of chronic pain who are new to medicated care or wary of negative outcomes.

If meant to target sufferers of the condition it seeks to alleviate, then the commercial’s objective is identical to that of most other commercials: to make a viewer remember the product and move towards obtaining it. In the case of OxyContin, the ideal viewer would bring up OxyContin with their doctor, who would then supply a prescription to the patient.

But that’s just the problem.

The Purdue Pharma commercial wants people in pain to become prescription OxyContin users. However, the scientific study from which the commercial’s 1% addiction rate statistic is pulled does not apply to prescription OxyContin users. It applies only to patients undergoing hospitalized, regimented care – a very different environment to self-administration.

The commercial isn’t untrue – it does specify the 1% addiction rate applies to “patients treated by doctors”, but if we assume the viewer was meant to understand this, then who would be this commercial’s ideal viewers? What group of people were Purdue Pharma hoping would act on this message, and use OxyContin?

- Patients suffering from chronic pain who are currently

hospitalized?

- No, a doctor administering hospital care to a patient would be highly unlikely to accept a patient’s suggestions on which medications to use, especially based on something they just saw on TV.

- Doctors working in hospitals?

- No, this clip doesn’t contain nearly enough information to convince a doctor to switch to OxyContin. It even fails to cite the origin of its 1% addiction rate statistic.

The most probable audience is the one mentioned above – persons at home who were or knew of someone suffering from chronic pain. Unless Purdue decided to dedicate half of its commercial to information that meant nothing to its target audience, then it appears most likely that the company hoped viewers would misinterpret the quote. After all, “patients who are treated by doctors” could simply refer to those receiving prescriptions from doctors. It’s an easy mistake to make – a mistake that would hugely benefit Purdue Pharma.

In spite of this, the letter’s popularity flourished . The New England Journal of Medicine’s website notes this letter has been cited nearly 400 times. Google Scholar notes it has been cited 1,243 times.

As its popularity snowballed, the lines between ‘topical’ and ‘importance’ began to blur. A 2001 TIME Magazine feature article titled Less Pain, More Gain cited it as a “landmark study”, but its own author scarcely remembers it. Quinoes couldn’t even find a full text record of the study, reporting that it had been unavailable from its journal’s archives for at least ten years.

This seems to suggest that most citations were based on the article’s four-sentence feature, with public perceptions of its importance possibly based solely upon its citations by TIME, Purdue, and other prominent names.

In the midst of the current opioid crisis, researchers are devoting more time into conducting more extensive reports on this statistic – reports that show addiction rates to be far higher than Purdue’s marketing would have you believe.

One of the more credible studies, cited by the National Institute on Drug Abuse on their webpage “Opioid Overdose Crisis”, is a 2015 study titled Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Focuses specifically on opioid misuse, looking at average prevalence rates among patients in 38 studies. The article notes the range of reported problematic use was enormous, ranging from less than 1% to more than 80%.

However, the study calculated average rates of misuse to be between 21% and 29%, and rates of addiction between 8% and 12%.

Other, more recent studies that examine additional factors indicate those rates are far higher among specific populations. A study published in the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, for example, cites the rates of adverse effects of opiate medications to be somewhere around 30%.

The article’s lead author Kevin Bain, MPH, PharmD, co-founder and medical director at Biophilia Partners, said that while the 30% described does not specifically denote addiction rates, it could still be highly relevant to the addiction process.

“The concern we have is that patients may not get the proper amount of pain relief due to an undetected interaction with some other medications they’re taking,” said Dr. Bain in a press release. “That can lead to them taking higher doses of their prescribed opioid and more frequently, which over time can lead to a substance use disorder or even an overdose.”

Bain goes on to stress the importance of informing doctors of current medications, and recommends patients stagger their medications to help avoid problematic drug interactions. Numerous other recent studies have pointed to other factors regarding the prevalence of Opiate Use Disorders (OUDs). Possible influences vary widely, including pregnancy, ADHD, and just about everything in between.

Oxycontin is a complicated drug, with hundreds of thousands of patient testimonials warning bystanders away from its seller’s false promises. If the pharmaceutical industry had held patient reports in as high esteem as lab reports, our nation might have dodged much of the tragedy we face today.